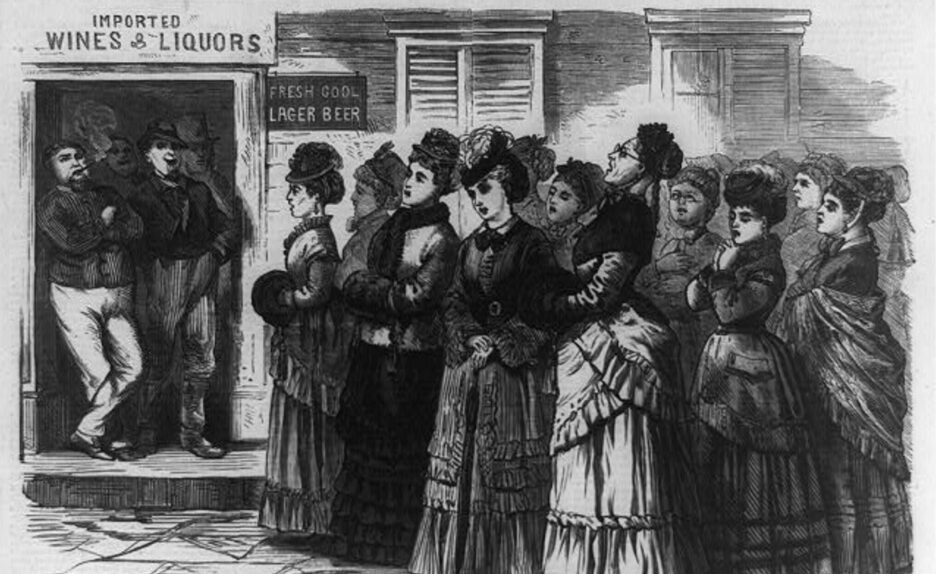

When people thought of Butte in the early 1900s, prior to prohibition, they thought of a, “wide open town,” where sex workers walked to streets, gambling was accepted and alcohol flowed at all hours of the day. But this was only the case for men. Men could publicize and indulge in their vices during broad daylight without concerns over arrest.

Montana’s legislature reinforced this mindset in 1907. A new law banned women from saloons, forcing owners to dismantle spaces designated for female drinkers. “Winerooms–the partitioned areas in which some saloon owners permitted women to drink–were considered incubators of prostitution.”(1)

Carrie Nation–or better known as Hatchet Granny–was a woman of fame, controversy, and temperance, opposing alcohol before prohibition. She was remembered as visiting establishments who served alcohol with a hatchet in hand. In January 1910 she visited Butte for the first time. Records state she would march up Arizona Street to Mercury, giving anti-drinking speeches and pleading with saloons to close.

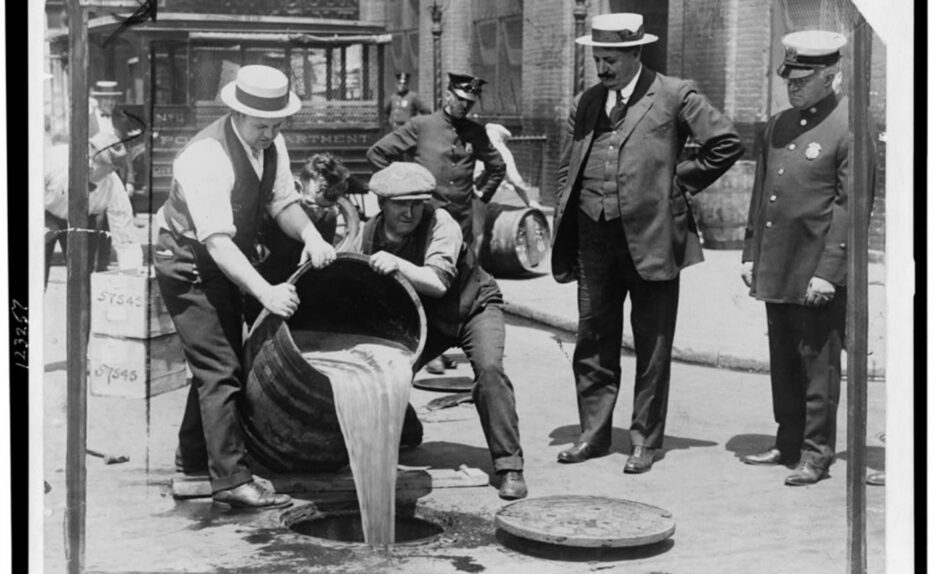

While most of Butte didn’t agree with Hatchet Granny, many other Montanans did. Groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were able to persuade voters that alcohol was evil. It would take two years after voting, late 1918, for prohibition to begin in Montana–at least on paper. The rest of the nation would follow by going dry at midnight on January 17, 1920.

Butte, an area where prohibition had been adamantly rejected, felt little to no effect. Law enforcement would look the other way and many officers were accepting alcohol as a form of bribery. The economy relied on it and, instead of serving it at the bar, spirits were moved underground, sometimes literally, to speakeasies, out of sight from the public.

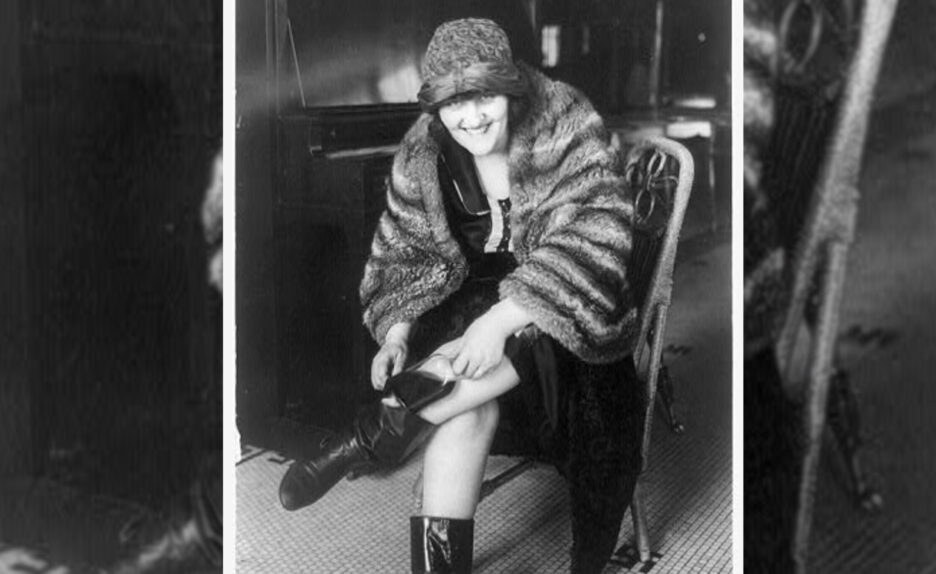

And while Prohibition may have created some challenges in communities like Butte, it offered women a chance to revolutionize the distilling industry and forever changed what was considered to be a male-dominated profession. It helped that, if caught, women received little to no punishment and could return right back to distilling.

The concept of women making alcohol was so unheard of at the time that police would look for any reason to charge a man for a crime even when the evidence pointed to a woman perpetrator. In 1922, a Federal Prohibition Officer was driving his car on Nettie St. before it broke down. Going to a neighboring home for assistance, he found Maud Vogen and her mother working a 20-gallon still. Despite being caught in the act, police were convinced it was her husband, Andrew, but investigations showed they had not been living together for some time. When questioned, Andrew denied all knowledge of the still and police were forced to revolutionize their preconceived notions on what women could do.

“In the 1920s judges and juries alike, whose previous contact with female criminals had been almost exclusively with prostitutes, were confounded by gray-haired mothers appearing in their courts on bootlegging charges.”(2)

“In all aspects of the liquor business, women moved into spaces that had once been reserved exclusively for men.” This was the first step in transforming rigid gender roles that had a firm grasp on how women were to act before prohibition. Drinking, “was one of the most gender-segregated activities in the United States.”(1)

To make extra income, and to provide themselves with booze, women took up bootlegging. Hiding their activities from husbands was easy. At this time women were mostly housewives that knew their husbands routines and the areas of the home they would and would not visit. Hiding a still and mash in those areas guaranteed, for most of them, that their husbands would never even notice. Using milk bottles, women hid and moved alcohol to market, sometimes with the help of the local milkmen.

Women were thriving. But, unlike how the Federal Prohibition Officers would claim, it wasn’t just to indulge in personal vices.

Nora Gallagher was a Butte widow with five children. As time passed, money became tighter. Then the idea came–moonshining. She brought a 50 gallon still home and started distilling. When arrested and brought to trial in 1921, she explained she was moonshining to dress her five children in nice clothes for Easter.

Bootlegging became synonymous with independence for women. It gave women an avenue to consider what they were capable of doing, rather than what they were supposed to do.

Drinking during Prohibition became an equal-opportunity vice.

Men were surprised–and put off–to find women bellying up to the speakeasy next to them. The owners, who no longer had gender segregated bars, welcomed everyone with open arms. When you’re already breaking the law, why would it matter who you’re serving to?

Women also ran their own speakeasies, “moonshine joints” or “blind pigs.” Sometimes with their husbands but often on their own, capitalizing on the success of making their hooch and selling it too.

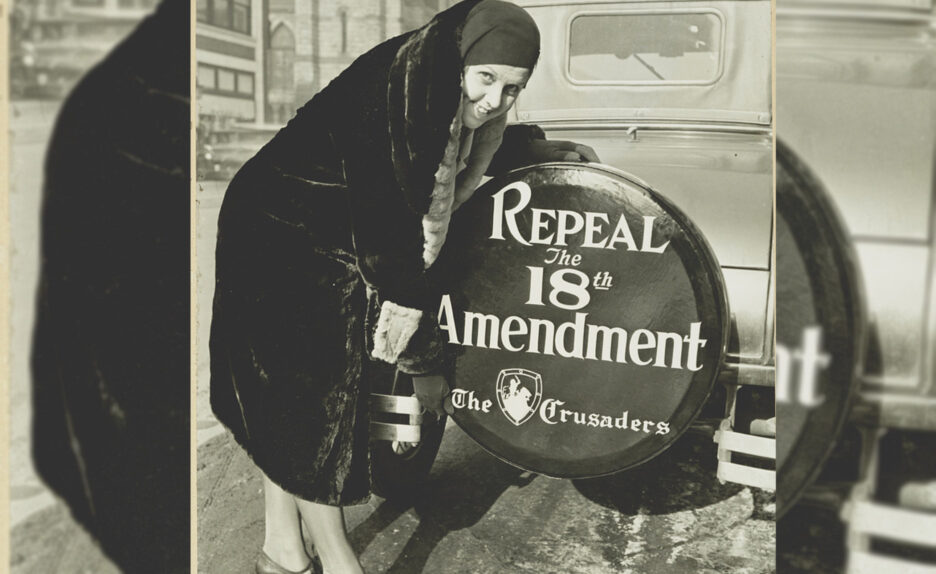

In 1926, Montana was the first state to repeal prohibition–seven years before the nation would repeal it in 1933.

Representatives considered the prohibition experiment a failure. Lost tax revenue, the high cost of policing with little return and an increased percentage of the population who actually started drinking persuaded Montana to repeal prohibition.

“Peer pressure, as well as the lure of the forbidden, was clearly at work. Alma Muentzer Hilemann recalled that none of her girlfriends drank until Prohibition, “then everybody ha[d] to taste and see what it [was].”(1)

Today, this rich, if not quite legal legacy lives on in Butte. From the historic speakeasies to the hidden tunnels and pathways connecting office buildings to bars, Butte hasn’t lost the connection to this element of its past. And it lives on at Headframe, too.

Everyone is welcome to belly up to the bar at Headframe. We are proud of the generations of distillers–both men and women–who came before us and we honor their legacy with our milk bottle inspired custom bottle shape. We honor them with our diverse team of distillers who make, sell and serve the spirits at Headframe. And we honor them by continuing the legacy of distilling in Butte, America.

- Murphy, Mary. “Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana.” American Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 2, 1994, pp. 174–94

- Murphy, Mary. “Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41.” Women, Gender, and Sexuality in American History

When John and Courtney McKee purchased the Schumacher Building on 21 S. Montana Street, they purchased a piece of Butte history with the goal of breathing new life into it. When the McKees searched through the contents of the building, which included the old Pioneer Club located on the top floors, they found an original copy of an Abstract of the property showing it was prepared for William Clark – the previous owner of the site.

The Abstract included two copes of a hand drawn map, showing the existing mine lodes located on the property. There were four; one of which was the Destroying Angel.

With this new information, the McKees brought these documents to the attention of Dick Gibson, a local Butte historian, and asked him what he knew about them. Dick researched the Destroying Angel and prepared this following report for the McKees,

“Lee Mantle was a business man and politician born in England in 1851. Soon after he arrived in Butte in 1877, he was managing the town’s first telegraph office and owned the first insurance company in the growing community. He was one of the first aldermen after Butte was incorporated in 1879, and established the Intermountain Newspaper. After a term as Mayor of Butte in 1893, he served in the U.S. Senate from 1895-1899. He also owned the brothel on Mercury Street – now known as the Blue Range building [torn down in 2021]. His home at 213 N. Montana is the present-day Duggan-Dolan Mortuary.

Mantle dabbled in mining and, in the late 1870’s or early 1880’s, established the Diadem Lode Claim, a narrow block that extended from Montana Street between Broadway and Park to the intersection of Galena and Main and a bit beyond.

This was in the middle of the Butte town site, and area that was fast becoming occupied by homes and businesses. In 1882, Mantle and his partners sought to evict the surface landowners and their businesses from the Diadem Claim.

The surface landowners and businessmen reacted by banding together to defend against Mantle’s lawsuit. This group felt that there was a ‘flaw’ in Mantle’s filing of the Diadem Claim and together, with legal counsel, they established a new claim that would encompass the Diadem and go beyond, for the express purpose of defeating Mantle and the Diadem claim owners. That new claim was called the Destroying Angel, an ‘ominous name’ intended to reflect the result for Mantle and his allies.

The Destroying Angel Claim’s boundaries ran just inside the block on the west side of Montana Street, from Broadway to Galena [including the land beneath Headframe today] and angles slightly southeast to a line about halfway between Main and Wyoming Streets. The partners in the Destroying Angel Claim agreed to pay into the claim, and its expenses in fighting Mr. Mantle, proportionally to their ownership. They won their challenge to Mantle’s attempts to evict them, and Mantle’s claim was dismissed in 1884.

Then, the partners began to fall upon each other. In 1887, it was alleged that some of the partners had not paid their fair share. Among them they had contributed $1,445.53 toward the case, but allegedly $1,900 was spent and not all the partners had contributed to the $450 in excess costs.

There was also confusion and difference of opinion about surface ownership of parts of the claims that had no existing lots. Some felt that there was to be a pro-rata distribution of the surface land that no one owned. Others felt that when they prevailed on Mantle, ownership would simply reflect what they already owned. A lower court held that the contract among the parties had no mistakes that mattered. The Montana Supreme Court ruled in 1889 that the claims of errors and conflicts were irrelevant and upheld the lower court decision.

But it wasn’t over yet.

In 1895, another case involving some of these partners reached the Montana Supreme Court on appeal from the Second Judicial District of Silver Bow County. This time it was a squabble between most of the group (Thomas et al.) and one V. Frank, who had, they claimed, agreed to pay $200 against the $450 excess mentioned in the pervious case. Yet another member of the group’s pro-rata assessment had owed $41.25, but he had defaulted on that payment, so in lieu of payment he sold his lot to Frank.

The deed of sale did not include a price; Frank reportedly said he didn’t care what they filled in for the sale price. An amount of $200 was filled in, with the notary going between the two parties. The plaintiffs sued to recover the $200. The defendant denied everything, more or less casting aspersions on the go-between notary. An earlier jury trial found for the plaintiffs; the defendant appealed to the Montana Supreme Court. The MSC, in a decision on June 10, 1895, found in favor of the plaintiffs, and ordered the defendant to pay the $200 plus interest.

There was, apparently, a Destroying Angel Mine established on this contentious claim. From 1895 to 1910, the location is given as 35 W. Galena Street, a space that is a vacant lot of the 1900 Sanborn map. This is on the edge of Chinatown, but near the center of the Destroying Angel Claim. This is also almost exactly the location indicated for the Destroying Angel Mine on the 1912 map by Walter Harvey Reed.”

References:

Progressive men of the State of Montana, ca. 1901 Case law, reports of Montana Supreme Court Decisions Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives, Polk City Directories Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, Montana Memory Project, U. of Montana – Maps USGA Professional Paper 74: Butte Mining District, by W.H.Weed.