Butte, Montana, once the Richest Hill on Earth, owes much of its storied past to the three Copper Kings, William A. Clark, Marcus Daly and F. Augustus Heinze. These industrial titans fiercely competed over copper, shaping our economic and social landscape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

William A. Clark: The Wealthiest Man of the Gilded Age

William Andrews Clark transitioned from gold to copper mining during Montana’s gold rush, amassing immense wealth through mining, banking and railroads. A powerful businessman and U.S. Senator, Clark’s influence extended far beyond Butte, even though his Columbia Gardens amusement park gave everyone a reason to stay. Towns like Clarkdale, Arizona and Clark County, Nevada are named after Clark and his mining efforts. Addicted to the finer things in life, he spent his last days in his New York mansion on Fifth Avenue.

Marcus Daly: The Irish Immigrant Who Built an Empire

Irish-born Marcus Daly became a key figure in Butte’s mining scene in the 1870s. Leading the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, Daly’s strategic acquisition and development of the Anaconda mine turned it into one of the world’s largest copper producers. Known for his investments in smelting facilities and improved working conditions for miners, Daly’s contributions significantly boosted Butte’s growth. Montana Tech, the local Butte college, has a statue of Marcus Daly at the entrance of their campus honoring his work that put people over profit.

F. Augustus Heinze: The FORGOTTEN COPPER KING

Fritz Augustus Heinze, a young engineer from Brooklyn, was 19 when he arrived in Butte in the late 19th century. Heinze’s innovative mining techniques and aggressive legal strategies allowed him to compete effectively with Clark and Daly. His use of the Apex Law to claim ore bodies led to numerous high-stakes courtroom battles, highlighting his relentless pursuit of success. By 1906, he too was tired of the Butte battles and left for New York where he passed in 1914.

The Battle for Butte: Competition and Consequence

The rivalry between Clark, Daly and Heinze was intense and often ruthless, spurring technological advancements and economic growth that transformed Butte into a bustling metropolis. Their ambitions and battles put Butte on the map, making it a symbol of the transformative power of industry.

Butte’s Copper Kings paved the way for those who continue to push forward. Clark, Daly and Heinze all knew that it takes raw effort, hard work and a willingness to risk it all to be a Modern Maverick of their time.

We take extra care with our Copper King Whiskey Collection, with every special barrel finish proving that it isn’t how you start, but how you finish. Hand-crafted in honor of history, Butte Mavericks get shit done.

Headframe Spirits, a distillery located in Butte, has been honored as the 2024 Montana American Single Malt Distillery of the Year. This accolade recognizes Headframe’s outstanding contributions to the American Single Malt Whiskey industry and its commitment to excellence.

“When you think of single malt whiskeys you probably think of Scotch or Japanese single malt whiskeys,” notes John McKee, owner and founder of Headframe Spirits. “Headframe would like to introduce you to American single malt whiskeys with the Kelley American Single Malt Whiskey.”

This announcement is confirmed as Headframe’s Kelley American Single Malt Distiller’s Select whiskey also received gold marks during this year’s spirits competition, scoring 95 points.

“It’s an honor to receive a gold for our Kelley Distiller’s Select,” said Blake Mueller, head distiller at Headframe Spirits. “Each Distiller’s Select barrel is hand-picked by the distilling team and sold exclusively in our Tasting Room. Not just with our tastes in mind, but with attention to the differing pallets of everyone that comes to Headframe.”

The awards, bestowed by the New York International Spirits Competition, highlight Headframe’s innovative spirit, superior production techniques and the unique flavors that distinguish its American Single Malt Whiskey.

With over +1400 spirit entries from 39 countries and 38 states across the US, Headframe notes it’s rewarding to see their spirits stack up against some nationally recognized distilleries – especially because whiskey production is a waiting game.

“We opened this distillery to make an American Single Malt,” said McKee. “At the time, 12 years ago, no one was doing this. As the largest American Single Malt distillery west of the Mississippi, Headframe is so proud to have won this award and we can’t wait for you to experience our American Single Malt whiskeys for yourself – both in the Kelley American Single Malt and a new release set for later this month.”

In celebration of this milestone, Headframe will release a new American Single Malt – the Copper King. Aged for 5 years, finished in Cognac barrels and crafted in honor of Modern Mavericks, the Copper King will be released during a special event at Headframe on Thursday, June 27th. The event will feature a tasting of their award-winning American Single Malt Whiskeys plus the first taste of Headframe’s new Copper King American Single Malt they are adding to their spirits profile.

“Barrel finishes are always fun, they give us a playground to experiment with different flavors and create fun relationships with other people doing interesting work,” said Mueller. “It also helps keep the creativity and passion at the front and center of our efforts by giving us something unique we can share with the world.”

Headframe Spirits has quickly established itself as a leader in the American Single Malt category. In 2016, Headframe Spirits joined 8 other distilleries to found the American Single Malt Whiskey Commission to address the growing need for an elevated American-based product protected by federal category classification.

An American Single Malt is classified as 100% malted barley, distilled entirely in one distillery and mashed, distilled and matured entirely in the US. Headframe noted their success lies in the unwavering commitment to using Montana-sourced products from start to finish. By partnering with Montana farmers and a neighboring malt facility, the distillery ensures that the grains used in their spirits are of the highest quality and sustainably grown. Every spirit Headframe creates not only supports the local agricultural community but also guarantees a unique and authentic flavor profile that is true to Montana.

The tough winters of Butte craft tough people. Parents and grandparents recount walking, “both ways uphill in the snow,” to children. A reality of the Richest Hill on Earth rather than an exaggeration.

It takes tough people to handle what, on the surface is considered, harsh weather conditions. But in Butte, we know and love this seasonal comfort.

We love it because of what the snow creates. Cozy evenings, crackling fires and warm memories for years to come made under the blanket of snow that holds our Community close.

During the heart of winter, a quiet transformation takes place overnight. A yearly renewal of our mining city.

Rooftops become sugar-coated dreams and the ground a blank, shimmering canvas of endless possibilities. Clashes of light, white flakes sleep on the hard, steel headframes dotting the landscape.

People drift through the streets with steaming beverages in hand during Butte’s annual Christmas Stroll. Neighborhoods acquire the faint smells of burning firewood as chimneys puff to life. Snowmen and women start to line the streets as new memories are hand-crafted with those we love.

Yet, the beauty of snow lies not in its physical form but in its short lifespan. It cannot be captured or contained; it must be savored in the moment.

At Headframe, we cannot capture snow in a bottle, but we can bottle the feeling that winter brings. Swirling, shimmering warmth found in our Montana snow is encapsulated in our Snowdrift Seasonal Sweet Cream Liqueur.

Much like the snow that melts in the spring, our Snowdrift Sweet Cream Liqueur is ephemeral.

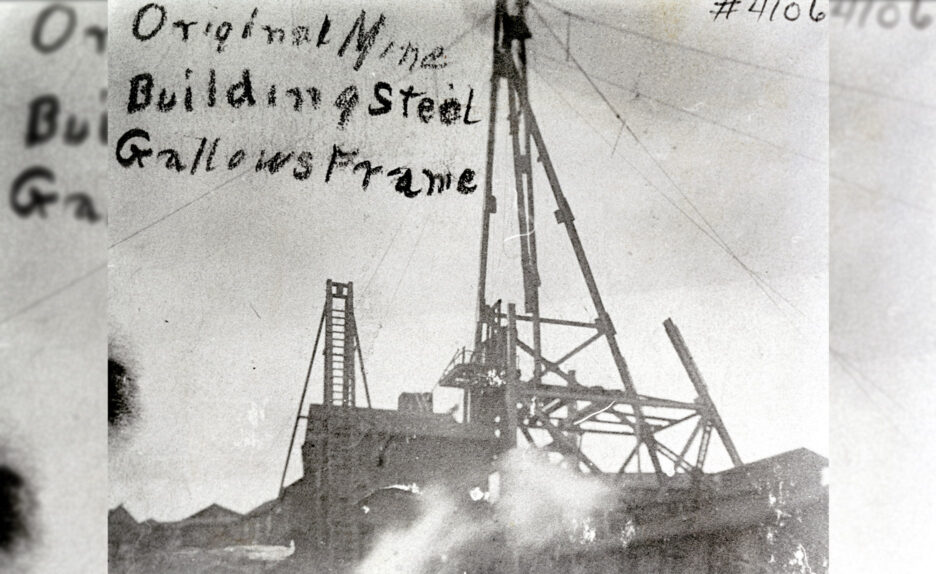

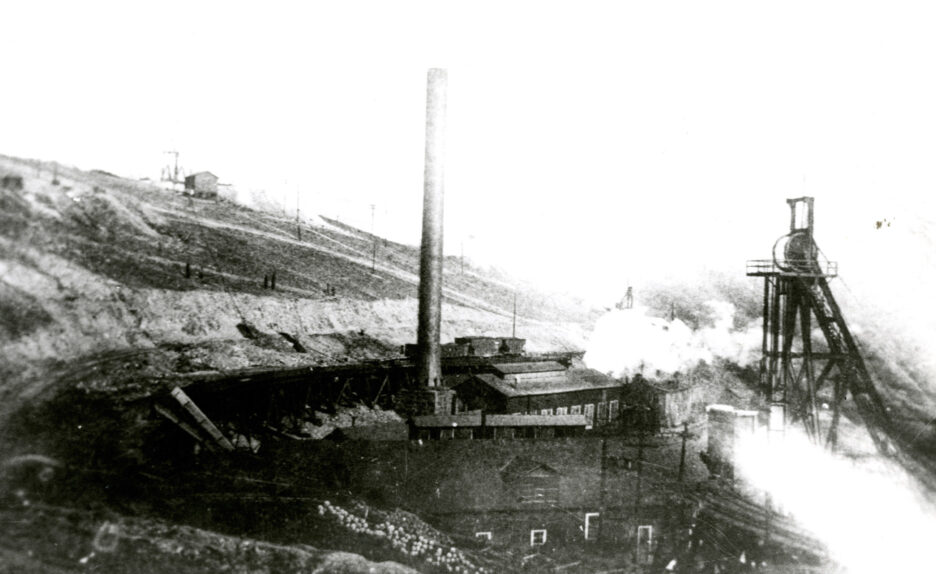

A shining example of adaptive reuse in Butte stands in the middle of Uptown at the Original Mine Yard.

Thousands of people dance together, swaying to the music during the annual music festivals that found their home in our mining town.

In its current state, it’s hard to believe that a location such as this was once a place where men gathered to put in the daily grind. The steel headframe that used to mean harsh working conditions is now used in celebration for weddings, concerts and so much more.

“We probably do 20 to 25 events up there throughout the year,” noted Bob Lazzari with the Butte Parks and Recreation.

Rebuilding of the Original began in 2007 led by Butte-Silver Bow County in coordination with the Environmental Protection Agency. It started after Butte was selected to host the National Folk Festival.

Things like a new roof on the hoist house and converting the headframe to a proper stage space transformed this once desolate space into a known location that hosts more than 165,000 people annually.

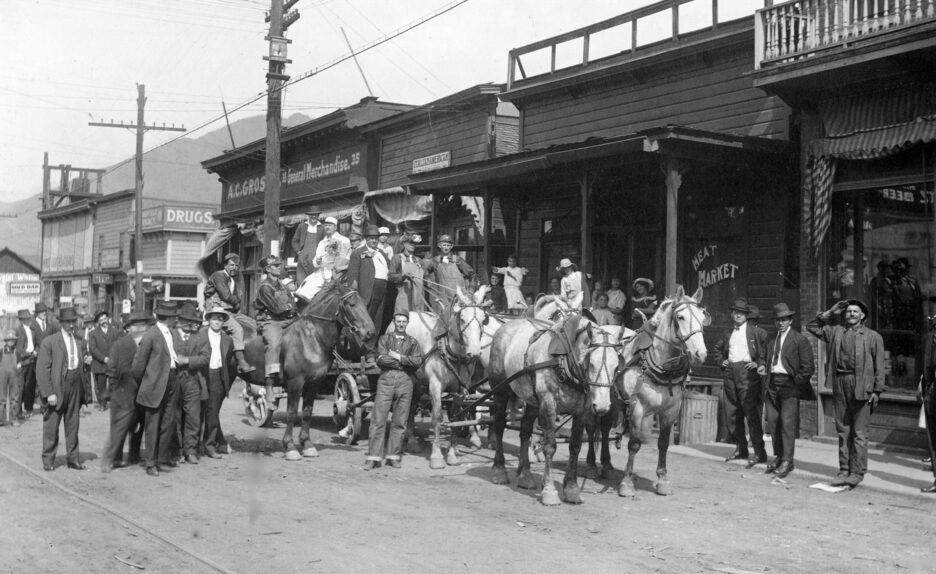

Images courtesy of the World Museum of Mining

Now, the Original illuminates the night as one of the few headframes decorated in red lights. It’s an effort to highlight the remaining bits of Butte heritage that dot our landscape – the headframes that helped us light up the world.

“The Original Mine Yard is now a crown jewel of the city,” said Jon Sesso in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) document. A re-imagination of what Butte’s historical assets can become – a symbol of the future.

Much like the transformation of the Original Mine Yard and electricity across the globe, good things take time to craft. Our Original X Rye Whiskey rested for ten years before being released to the public. In honor of raw effort and patience, enjoy it in celebration for weddings, concerts and so much more – or sip it under the Original headframe during the next big event.

I love the legislative process in Montana. For 90 days every other year, representatives of Montana—rural and urban, native and non-native, young and old, all genders, all backgrounds, all career histories—come together to write and revise laws for all Montanans. I don’t always love the outcomes of the work, but I do love the very democratic process.

Headframe has participated in the legislative process since 2011, before our distillery was open, because John was out of work and had time to lobby on behalf of the Montana distiller’s shared interests. At that time there were only a small handful of distillers in Montana and it was easy to build an agenda and go after it. Time has passed and that process has changed quite a bit. It’s gotten much harder in some sessions but this last session was fantastic. And while distilleries, and opinions, in Montana continue to evolve, we all share the ability to come together around shared goals.

Some back story: when Headframe opened our Tasting Room in 2012, we believed we were beholden to the same operating hours as breweries which can serve until 8pm and allow people to consume what they’ve been served until 9pm. After a couple years in operation, we learned we were mistaken about the parity in hours. The distiller’s laws were written in a different section of the code and the associated rules were interpreted differently. All of a sudden, we needed to stop serving early enough to kick our customers out of the Tasting Room by 8pm. It wasn’t a feel-good experience, but laws and rules are written for a reason and I’m a big believer that (most) laws should be followed and if we don’t like them, we should work to change them.

SB 209, a bill introduced and passed this last session, gives distilleries the consumptive hour we thought we’d had all along. Now, customers are allowed to be served until 8pm and enjoy their cocktails in the Tasting Room until 9pm. And, as an added bonus, the bill also increased daily bottle sales from 2 bottles to 6 bottles (more specifically, from 1.75 liters to 4.5 liters per person per day). Senator Greg Hertz from Polson sponsored the bill and Governor Gianforte signed it last week. The Montana Distiller’s Guild and our lobbyist Jen Hensley were instrumental in getting this bill introduced and keeping it alive despite challenges.

12 years ago, it was enough for some scrappy distillers to show up and work on behalf of bills we wanted but time has passed and the landscape changed. Now, showing up with some savvy and some expertise is beneficial. It’s great to have a lobbyist who understands our business and our interests and knows how the process works well enough to navigate the politics on our behalf. It’s also great to have a woman represent our industry in a way that speaks to our shared industry values of job creation, value-added agriculture and economic impact.

Being able to serve until 8pm is wonderful. Being able to sell 6 bottles will be great for tourists and for special release products. And these rules aren’t beneficial only for Headframe but for all distilleries, their customers and communities.

So here’s to a success at the 2023 Montana Legislature. While we may not love all of the change that’s come out of this session, it’s pretty great to celebrate this bipartisan win and the people who came together to get us here.

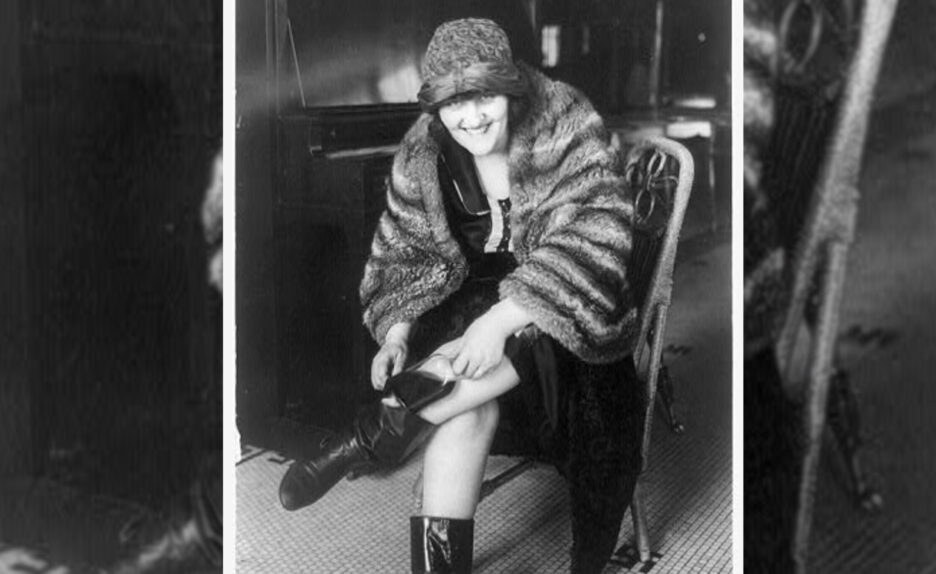

When people thought of Butte in the early 1900s, prior to prohibition, they thought of a, “wide open town,” where sex workers walked to streets, gambling was accepted and alcohol flowed at all hours of the day. But this was only the case for men. Men could publicize and indulge in their vices during broad daylight without concerns over arrest.

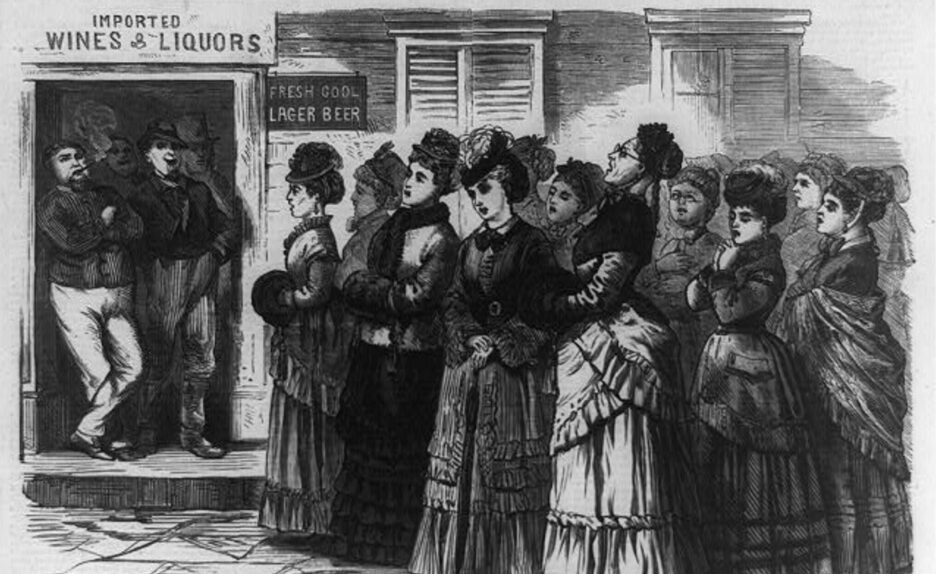

Montana’s legislature reinforced this mindset in 1907. A new law banned women from saloons, forcing owners to dismantle spaces designated for female drinkers. “Winerooms–the partitioned areas in which some saloon owners permitted women to drink–were considered incubators of prostitution.”(1)

Carrie Nation–or better known as Hatchet Granny–was a woman of fame, controversy, and temperance, opposing alcohol before prohibition. She was remembered as visiting establishments who served alcohol with a hatchet in hand. In January 1910 she visited Butte for the first time. Records state she would march up Arizona Street to Mercury, giving anti-drinking speeches and pleading with saloons to close.

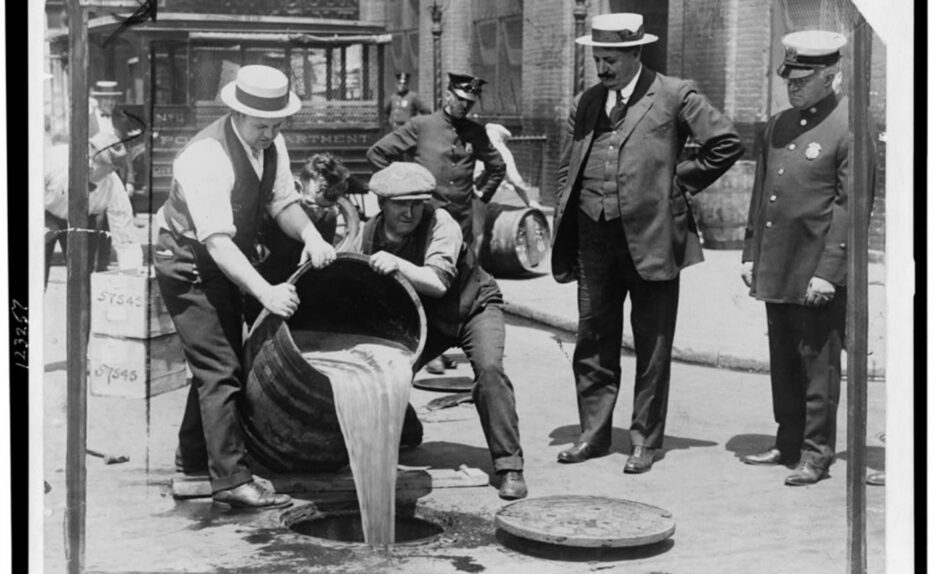

While most of Butte didn’t agree with Hatchet Granny, many other Montanans did. Groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were able to persuade voters that alcohol was evil. It would take two years after voting, late 1918, for prohibition to begin in Montana–at least on paper. The rest of the nation would follow by going dry at midnight on January 17, 1920.

Butte, an area where prohibition had been adamantly rejected, felt little to no effect. Law enforcement would look the other way and many officers were accepting alcohol as a form of bribery. The economy relied on it and, instead of serving it at the bar, spirits were moved underground, sometimes literally, to speakeasies, out of sight from the public.

And while Prohibition may have created some challenges in communities like Butte, it offered women a chance to revolutionize the distilling industry and forever changed what was considered to be a male-dominated profession. It helped that, if caught, women received little to no punishment and could return right back to distilling.

The concept of women making alcohol was so unheard of at the time that police would look for any reason to charge a man for a crime even when the evidence pointed to a woman perpetrator. In 1922, a Federal Prohibition Officer was driving his car on Nettie St. before it broke down. Going to a neighboring home for assistance, he found Maud Vogen and her mother working a 20-gallon still. Despite being caught in the act, police were convinced it was her husband, Andrew, but investigations showed they had not been living together for some time. When questioned, Andrew denied all knowledge of the still and police were forced to revolutionize their preconceived notions on what women could do.

“In the 1920s judges and juries alike, whose previous contact with female criminals had been almost exclusively with prostitutes, were confounded by gray-haired mothers appearing in their courts on bootlegging charges.”(2)

“In all aspects of the liquor business, women moved into spaces that had once been reserved exclusively for men.” This was the first step in transforming rigid gender roles that had a firm grasp on how women were to act before prohibition. Drinking, “was one of the most gender-segregated activities in the United States.”(1)

To make extra income, and to provide themselves with booze, women took up bootlegging. Hiding their activities from husbands was easy. At this time women were mostly housewives that knew their husbands routines and the areas of the home they would and would not visit. Hiding a still and mash in those areas guaranteed, for most of them, that their husbands would never even notice. Using milk bottles, women hid and moved alcohol to market, sometimes with the help of the local milkmen.

Women were thriving. But, unlike how the Federal Prohibition Officers would claim, it wasn’t just to indulge in personal vices.

Nora Gallagher was a Butte widow with five children. As time passed, money became tighter. Then the idea came–moonshining. She brought a 50 gallon still home and started distilling. When arrested and brought to trial in 1921, she explained she was moonshining to dress her five children in nice clothes for Easter.

Bootlegging became synonymous with independence for women. It gave women an avenue to consider what they were capable of doing, rather than what they were supposed to do.

Drinking during Prohibition became an equal-opportunity vice.

Men were surprised–and put off–to find women bellying up to the speakeasy next to them. The owners, who no longer had gender segregated bars, welcomed everyone with open arms. When you’re already breaking the law, why would it matter who you’re serving to?

Women also ran their own speakeasies, “moonshine joints” or “blind pigs.” Sometimes with their husbands but often on their own, capitalizing on the success of making their hooch and selling it too.

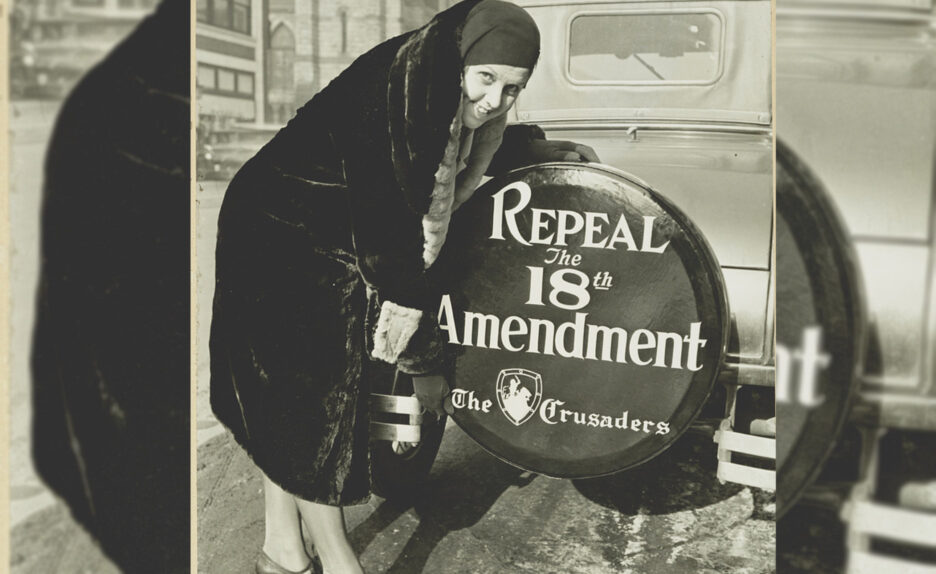

In 1926, Montana was the first state to repeal prohibition–seven years before the nation would repeal it in 1933.

Representatives considered the prohibition experiment a failure. Lost tax revenue, the high cost of policing with little return and an increased percentage of the population who actually started drinking persuaded Montana to repeal prohibition.

“Peer pressure, as well as the lure of the forbidden, was clearly at work. Alma Muentzer Hilemann recalled that none of her girlfriends drank until Prohibition, “then everybody ha[d] to taste and see what it [was].”(1)

Today, this rich, if not quite legal legacy lives on in Butte. From the historic speakeasies to the hidden tunnels and pathways connecting office buildings to bars, Butte hasn’t lost the connection to this element of its past. And it lives on at Headframe, too.

Everyone is welcome to belly up to the bar at Headframe. We are proud of the generations of distillers–both men and women–who came before us and we honor their legacy with our milk bottle inspired custom bottle shape. We honor them with our diverse team of distillers who make, sell and serve the spirits at Headframe. And we honor them by continuing the legacy of distilling in Butte, America.

- Murphy, Mary. “Bootlegging Mothers and Drinking Daughters: Gender and Prohibition in Butte, Montana.” American Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 2, 1994, pp. 174–94

- Murphy, Mary. “Mining Cultures: Men, Women, and Leisure in Butte, 1914-41.” Women, Gender, and Sexuality in American History

“We’re here to celebrate 10 years in operation and 10 years is a Big Damn Deal. But that success doesn’t belong just to Headframe or just to me and John, it belongs to Butte. It belongs to all of us.

You likely already know what we do, but in case you don’t, in the last 10 years, Headframe has opened and operated a distillery where we make our own spirits, run a Tasting Room, where we welcome the public and the community to share what we do and connect with one another. We also built a Manufacturing division where we build stills, which we sell to clients all over the world. Many of our clients are small businesses like us, looking to add value to their own communities and we are proud to serve them. We also do contract distilling work, which enabled us to open the largest Single Malt Whiskey distillery west of the Mississippi, utilizing 18,000 pounds of Montana grain daily.

When we started Headframe, we never imagined what it would be today.

John was raised here and we love living here. In 2010, John lost his job building biodiesel refineries–essentially big biodiesel distilleries–around the midwest. We were living here, raising our kids here and John was traveling a lot for work. When he lost his job, we had to either leave to chase biodiesel jobs or stay and find something new for John to do. John knew distillation. He loved a good cocktail. And we both loved Butte. So we stayed and used what he knew to create Butte’s first ever legal distillery. (I say legal because we all know there’s been plenty of booze made without a license in Butte’s past–and probably also her present).

Butte’s always been great at telling the stories of her past. I realized in 2010 as we were getting started, that Butte was in fact so good at telling the stories of her past that we weren’t telling the stories of our present or our future. We were so focused on what we had been, we forgot to keep writing the stories of what we would become as a community.

We built Headframe with respect for the past and an eye to the future.

Part of that means putting our community, and the people in it, first.

WITH YOUR HELP HEADFRAME HAS…

Donated over $350,000 to local organizations and charities.

Produced and delivered 6600 gallons of Hand Sanitizer.

Funded 27 breast and cervical screenings.

Hosted over 100 artists hosted with over $40,000 of art sold—and Headframe didn’t take a single penny in commission. That value belongs with the artists and it’s a privilege for us to be the display space for them.

Consumed over 3,121,469 pounds of grain.

Produced over half a million bottles of spirit.

Sold 28 stills out into the world.

Welcomed 12 Free Spirits Club winners.

Revitalized two buildings.

Created about 30 new jobs here in our backyard.

Had an economic impact of over $10 million in our community.

And are the proud creators of Montana’s favorite Spirit, the Orphan Girl Bourbon Cream liqueur and Montana’s favorite cocktail: the Dirty Girl.

And we’ve seen our community step up for the last 10 years – helping us write a story of Butte’s present that we are proud of. Even now, we are seeing places on every side of Headframe like Paper Cranes, the Dykman, Sláinte and the Colonial Apartment building be reinspired. Not by us, but by members of this community who believe in this neighborhood.

Great new uptown businesses like 5518, Pita Pit and Taco Del Sol, Sláinte, 51 Below, the Miner’s Hotel, Butte Brewing and North 46 have opened, each staking a claim, believing in Uptown Butte. Believing in their community to support them, believing that Butte’s future can and should be built on respect for Butte’s past.

NorthWestern Energy recommitted to Butte, building a beautiful new building in Uptown. The Finlen Hotel is under new ownership, still by people who live in and love this community and the Elks Club is thriving under great leadership.

WET–Water and Environmental Technology– continues to grow and lend its environmental restoration and remediation expertise to our community and many others across the country.

Other new buildings like the Emma Park Community center and the Uptown parking garage add to the beautiful Uptown landscape.

Almost every one of these projects, and certainly Headframe’s revitalization, couldn’t have happened without great support from Butte’s local government, the State of Montana and you.

Thank you for believing in your community. Believing in Uptown Butte, believing in Headframe and believing in me and in us.

What made this community bounce wasn’t someone from the outside making change, it was us–all of us. The dreamers and the doers and the shoppers and cheerleaders. We’ve done it together and there’s still more to come!

Earlier this year, Butte incorporated the Uptown Master Plan into the city’s comprehensive plan for the future. The Uptown Plan is full of vision, and concrete plans, for the Uptown and I’m proud of the work that’s been done and excited for the work that’s yet to come.

I believe in Butte. And you’ve been very gracious to read to my long winded love letter to you and to this place.

I want to share 3 things I’ve learned personally in the last 10 years

I thought, in opening a business–and not having any outside investors–that we would sink or swim on our own merit. Turns out, you sink or swim on the merit of the people you surround yourself with. I’m incredibly proud of the people on Team Headframe. We are what we are because of them.

I’ve learned that my two core values are Community and Courage. It’s been true my whole life, I just couldn’t name it until recently. Those values are why I’m standing here today and they’re “The Why” behind all of my actions and decisions. I encourage each of you to clarify your values and your purpose. Life is too short to live without purpose.

Lastly, I wasn’t born here, I’ve only been here 21 years, so I’ll never have the privilege of being from Butte. I did, however, make a Butte Boy, our son Cooper was born here, and I’m very proud of that. Despite me not being born here, I was born to be a Butte girl and I’m so grateful to all of you for having me!

I’m excited to share our rebrand with you. New website, new labels and new merchandise which our team has worked incredibly hard to bring to life for the last year. We did this because 10 years is a great time to reexamine the landscape and ask how we could do better.

Lastly, 10 years ago we named ourselves Headframe Spirits, after the legacy of this incredible place. When we started building stills, we called that Headframe Spirits Manufacturing. You have called us many things: Headframe, The Headframe’s, Headframe’s Distillery. We’ve joked you should call us whatever you want, just don’t stop calling us. Now we’ve made our name shorter and easier to remember: Headframe. One word to refer to everything we do.

Thank you for 10 years of making your dollar vote for Headframe and for the other small businesses in our community. We’re grateful for 10 years of love and support and look forward to many more years together.”

THANK YOU

Cheers, John and Courtney McKee

When John and Courtney McKee purchased the Schumacher Building on 21 S. Montana Street, they purchased a piece of Butte history with the goal of breathing new life into it. When the McKees searched through the contents of the building, which included the old Pioneer Club located on the top floors, they found an original copy of an Abstract of the property showing it was prepared for William Clark – the previous owner of the site.

The Abstract included two copes of a hand drawn map, showing the existing mine lodes located on the property. There were four; one of which was the Destroying Angel.

With this new information, the McKees brought these documents to the attention of Dick Gibson, a local Butte historian, and asked him what he knew about them. Dick researched the Destroying Angel and prepared this following report for the McKees,

“Lee Mantle was a business man and politician born in England in 1851. Soon after he arrived in Butte in 1877, he was managing the town’s first telegraph office and owned the first insurance company in the growing community. He was one of the first aldermen after Butte was incorporated in 1879, and established the Intermountain Newspaper. After a term as Mayor of Butte in 1893, he served in the U.S. Senate from 1895-1899. He also owned the brothel on Mercury Street – now known as the Blue Range building [torn down in 2021]. His home at 213 N. Montana is the present-day Duggan-Dolan Mortuary.

Mantle dabbled in mining and, in the late 1870’s or early 1880’s, established the Diadem Lode Claim, a narrow block that extended from Montana Street between Broadway and Park to the intersection of Galena and Main and a bit beyond.

This was in the middle of the Butte town site, and area that was fast becoming occupied by homes and businesses. In 1882, Mantle and his partners sought to evict the surface landowners and their businesses from the Diadem Claim.

The surface landowners and businessmen reacted by banding together to defend against Mantle’s lawsuit. This group felt that there was a ‘flaw’ in Mantle’s filing of the Diadem Claim and together, with legal counsel, they established a new claim that would encompass the Diadem and go beyond, for the express purpose of defeating Mantle and the Diadem claim owners. That new claim was called the Destroying Angel, an ‘ominous name’ intended to reflect the result for Mantle and his allies.

The Destroying Angel Claim’s boundaries ran just inside the block on the west side of Montana Street, from Broadway to Galena [including the land beneath Headframe today] and angles slightly southeast to a line about halfway between Main and Wyoming Streets. The partners in the Destroying Angel Claim agreed to pay into the claim, and its expenses in fighting Mr. Mantle, proportionally to their ownership. They won their challenge to Mantle’s attempts to evict them, and Mantle’s claim was dismissed in 1884.

Then, the partners began to fall upon each other. In 1887, it was alleged that some of the partners had not paid their fair share. Among them they had contributed $1,445.53 toward the case, but allegedly $1,900 was spent and not all the partners had contributed to the $450 in excess costs.

There was also confusion and difference of opinion about surface ownership of parts of the claims that had no existing lots. Some felt that there was to be a pro-rata distribution of the surface land that no one owned. Others felt that when they prevailed on Mantle, ownership would simply reflect what they already owned. A lower court held that the contract among the parties had no mistakes that mattered. The Montana Supreme Court ruled in 1889 that the claims of errors and conflicts were irrelevant and upheld the lower court decision.

But it wasn’t over yet.

In 1895, another case involving some of these partners reached the Montana Supreme Court on appeal from the Second Judicial District of Silver Bow County. This time it was a squabble between most of the group (Thomas et al.) and one V. Frank, who had, they claimed, agreed to pay $200 against the $450 excess mentioned in the pervious case. Yet another member of the group’s pro-rata assessment had owed $41.25, but he had defaulted on that payment, so in lieu of payment he sold his lot to Frank.

The deed of sale did not include a price; Frank reportedly said he didn’t care what they filled in for the sale price. An amount of $200 was filled in, with the notary going between the two parties. The plaintiffs sued to recover the $200. The defendant denied everything, more or less casting aspersions on the go-between notary. An earlier jury trial found for the plaintiffs; the defendant appealed to the Montana Supreme Court. The MSC, in a decision on June 10, 1895, found in favor of the plaintiffs, and ordered the defendant to pay the $200 plus interest.

There was, apparently, a Destroying Angel Mine established on this contentious claim. From 1895 to 1910, the location is given as 35 W. Galena Street, a space that is a vacant lot of the 1900 Sanborn map. This is on the edge of Chinatown, but near the center of the Destroying Angel Claim. This is also almost exactly the location indicated for the Destroying Angel Mine on the 1912 map by Walter Harvey Reed.”

References:

Progressive men of the State of Montana, ca. 1901 Case law, reports of Montana Supreme Court Decisions Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives, Polk City Directories Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, Montana Memory Project, U. of Montana – Maps USGA Professional Paper 74: Butte Mining District, by W.H.Weed.

On February 18, 1882, Butte threw a switch and joined New York City in the advancement of electricity. As one of the first places to experience such an excitement, miners knew that this revolution would bring a change to their city.

As the world electrified, the demand for copper continued to grow and with it, so did the increase in mines and headframes that now crown the Butte Hill. Against all odds, workers envisioned and erected these steel giants and used them to benefit not only the city of Butte, but the entire world. These stewards remain as inspiration to all of us in Butte as to what can be accomplished in our Community.

Here at Headframe, we look to our city for inspiration in everything we create – from our spirit names to the structural steel frames that support our stills. We believe that we can move forward and honor the legacy of Butte while creating more efficient equipment that not only makes more booze, but uses less energy to do so. Our continuous flow distillation system is capable of producing an assortment of beverage alcohols, from low to high proof spirits; faster, easier and cheaper than other technologies.

When you purchase a still from Headframe, you are supporting manufacturing in the United States and promoting jobs right here in Butte, America. Thanks to our clients, we continue to grow our facility and job opportunities for those in our community.

We build stills not only for ourselves, but for other distilleries all across the globe. We appreciate every opportunity to meet new people and share the story of our business and our place in the world – Butte, America.

When you walk into the Tasting Room at Headframe Spirits, there’s an instant sense of satisfaction even before you sample our handcrafted spirits. The first thing you’ll notice is the statuesque backbar that stands tall and proud to greet customers. Its meticulous wood work, beauty and strength has a story to tell. If only inanimate objects could speak of their incredulous journey.

The backbar came down the Mississippi River in 1906 by steamboat. Simultaneously, Gabriel “Teddy” Traparish immigrated to Butte from Dubrovnik, Croatia. He was 19 years old and single.

He aspired to be a businessperson, and Butte was a desirable place to achieve this dream.

Traparish fit perfectly in Butte. He had an outstanding work ethic, a goal driven mind and compassion and generosity for his community.

Traparish accomplished his goal after moving his way up the ranks, with long nights of working in bars.

In 1929, Teddy’s Rocky Mountain Cafe opened its doors in an Italian community named Meaderville. The Cafe would flood with the sounds of live music, dancing and delight from the patrons who filled it; finding relief after a long day’s work.

By 1935, his cafe was spotlighted, receiving attention from national magazines. The New York Times, Chicago Tribune and Saturday Evening Post spoke widely of the restaurant, the food and the people.

Teddy Traparish, who ended up becoming known as, ‘Mr. Meaderville,’ said, ”Henceforth, you will please forget New Orleans, refer Charleston to the rubble heap, abandon San Francisco, repudiate New York and dismiss Boston utterly. For Meaderville is the most incredible restaurant in (I swear) the world,” according to a 2004 Montana Standard article.

Photos provided by the World Museum of Mining

What was once Meaderville, is now the Berkley Pit. During the mining encroachment, underground mining transitioned to open pit mining causing the whole community to disappear. In 1961, Traparish chose to close his Rocky Mountain Cafe at 74 years old. Five years later, he donated his backbar to the World Museum of Mining.

John and Courtney McKee, the owners of Headframe Spirits, went to the museum before opening their doors. In it, they found Traparish’s backbar in the basement. They asked if they could display it in their distillery, thinking the least the owners could say is, no. The owners of the museum enthusiastically said, yes.

Headframe’s distillery was once home to a Buick dealership; although Traparish had a love for Cadillacs and would purchase a new one every year for almost 50 years, he wouldn’t be disappointed to know where his backbar stands today.

Mr. Meaderville was a restauranteur, a cadillac enthusiast and a genuine man. He never did marry or have children that would carry on his namesake. But, his legacy is carried from each newcomer and patron who are welcomed inside the doors, for Teddy resonates with the chatter of customers and the pour of our spirits alike.